Introduction

Astronomy is the oldest of the natural sciences dating back to ancient Chinese and Babylonian civilisations. It can be defined as the science that deals with the universe beyond the Earth.

Navigators, explorers and surveyors have used astronomical observations to determine their position on the Earth (latitude and longitude). Early surveyors, not only had skills in bushcraft, navigation and mapping, but they also required knowledge of mathematics and astronomy in addition to an understanding of the land and its potential.

The surveyor’s interest in astronomy was very much a practical one. Unlike the astronomer with a scientific interest in the stars, a surveyor was interested in how the stars could be used for the purpose of positioning on the Earth.

Surveying skills were an essential component of early Transit of Venus expeditions. It was often necessary to put more effort into the accurate geographic positioning of the observing location than into actually observing the transit. And it was often the case that a person with surveying expertise would complete the mathematical analysis of the observations.

Over the years, the work of surveyors using astronomy has been superceded by more modern positioning technologies such as the Global Positioning System (GPS). However the Transit of Venus observations which computed the scale of the solar system have provided the foundation of Modern Geodesy which impacts our lives in so many ways today.

The size and shape of the Earth is now monitored continuously using GPS, satellite remote sensing, high accuracy gravity sensing and other high precision, space-based measuring techniques. These provide the framework to enable scientific observation of climate change, sea level rise, mass water transport and global tectonic motion studies for earthquake prediction.

This knowledge enables many other mapping applications from land, mining and engineering surveying to smart phone apps and Geographic Information System functionality.

The convergence of these new high performance measurement technologies and unprecedented computing power has enabled what is being termed the “Geospatial Revolution”.

Career opportunities abound and a new generation of surveying and spatial professionals is encouraged to study these disciplines at Universities and TAFEs across the country.

Sailing south for a new sky

Sir Thomas Brisbane laid the foundation of Australian astronomy in 1821, but the record of astronomical observations made on Australian soil commences half a century earlier; as is well known, when Captain Cook was selected by the British Admiralty, chiefly for his astronomical qualifications, to conduct his famous expedition to the islands of the Pacific for the purpose of observing the transit of Venus of 1769, which he successfully accomplished at Otaheite (Tahiti).

After observing the transit of Venus, he discovered and visited several islands in the Pacific, and eventually re-discovered New Zealand, where he took formal possession of areas from both the main islands and accurately charted 3860 km of coastline for the first time.

Cook then sailed further westwards in his ship HM Barque Endeavor and sighted the south-eastern corner of the Australian continent on 20 April 1770. In doing so, he was to be the first documented European expedition to reach the eastern coastline. He continued sailing northwards along the east coast, charting and naming many features along the way.

On the 22 August 1770, he landed at what is now known as Possession Island and took possession of the eastern coast of Australia which he called New South Wales, in the name of Great Britain.

From Captain Cook’s astronomical observations made on Australia soil in 1770, was derived the first value on record of the longitude of Fort Macquarie (Sydney) viz. 151° 11 ‘ 32” east of Greenwich, which is almost identical with that determined by Capt. Flinders 33 years after (151° 11’ 49”).

Astronomical work done by Navigators and Explorers

Among the first buildings that were erected after the arrival of the “first fleet” commanded by Captain Phillip in 1788 was an observatory, which was erected on Dawes Point. One of the reasons for erecting the observatory was to observe the comet which was expected by Dr Halley (of Halley’s Comet fame) to return at the end of 1788 or early 1789 and would first be visible in the southern hemisphere.

For more than 30 years after the observation of the comet in Sydney, the astronomical record rests entirely on navigators and explorers.

It was during this period that surveys of the coast and explorations inland were being conducted by such nautical men as Bass, Flinders, Murray and King and the first inland explorers – Gregory, Blaxland, Oxley, Cunningham, Hume and others. Skilled astronomical observers and even accomplished astronomers were to be found among these navigators and explorers and the sun, the moon and the stars were no doubt closely watched and employed by them for the determination of their geographical positions.

Captain Matthew Flinders, who first circumnavigated Australia in 1802-3 on the Investigator and who first suggested calling the whole continent ‘Australia’, was an enthusiastic and most accurate observer of the heavenly bodies. The amount of Flinders’ lunar observations is remarkable, both for its quality and its quantity.

His value of the longitude of Fort Macquarie (Sydney) of 151°11’ 49” east of Greenwich, is within a kilometre of the true value which, considering the instrumental limitations and inaccuracy of the lunar tables in his day.

Captain King, the son of Governor King was sent by the British Government to complete the surveys of the coasts of New South Wales, which then extended from South Cape in Tasmania to Cape York. In these voyages, which extended over four years, Captain King in addition to his maritime discoveries and to the study of natural history in general, carefully determined the longitude of a number of important positions in the survey. He also observed transits of the moon and culminating stars over the meridian.

Surveyors and Astronomy

19th Century

Victoria

In 1853, shortly after legislation to establish the Colony of Victoria, Robert Lewis John Ellery was appointed in charge of the newly established Astronomical Observatory at Williamstown. This was established principally to make the necessary observations for the giving of time signals [via the dropping of the time ball at 1.00pm.] and the adjustment of sailing master’s nautical instruments. He was originally answerable to the Chief Harbour Master and then, when the jurisdiction of the Observatory was transferred, to the Department of Electric Telegraphs.

In August 1858, as part of a further Departmental realignment, Ellery and his equipment were again transferred, this time to the Surveyor General’s Department, to take responsibility for defining the geographical boundaries of the Geodetic Survey as proposed by Surveyor General Ligar. This survey would establish a system of astronomically determined divisions one degree each of latitude and longitude, marked on the ground, which would serve as the basis for further subdivision and, it was thought, be the most rapid and efficient method of making land available to the press of new selectors who were complaining of the lack of availability of land.

It was also to be the means of integrating and coordinating cadastral or Title surveys across the Colony, as deficiencies and errors in subdivisional surveys had become increasingly evident, leading to disputes and much official correspondence.

The 145th meridian was selected as the standard meridian as it was close to the Observatory. Whilst the meridians of longitude and parallels of latitude were run directly where possible, the Geodetic Survey also utilised triangulation as an integral part of the Survey to optimise their establishment, particularly in more distant areas of land demand in the Colony, such as Portland and Gippsland.

As an essential part of the triangulation, in 1860 an accurately measured base line was laid out at Werribee and connected very carefully to the triangulation network. A superb example of the marking [by a large dry stone cairn] of a triangulation survey station employed on the Survey still exists on Mt.Juliet, to the east of Healesville. For the young/fit it can be reached via a walking track starting from near Fernshaw Reserve.

In 1863 a new Astronomical Observatory commenced operation adjacent to Government House and the Botanic Gardens. The Magnetical Observatory, in the charge of Professor Neumayer, was also moved to these grounds from Flagstaff Hill.

Ellery had to combine his duties of the Geodetic Survey with those of the Observatory, which now included inter alia the provision of time to the Colony, the collation of rainfall records from across the settled areas and the calibration of various chronometers and barometers as well as his primary astronomical duties of observing Nebulae, the planets and any passing comets and publishing star catalogues.

At this time, the only other Observatory of British origin cataloguing southern stars was in South Africa. Astronomic observations necessary for the Geodetic Survey required the fundamental positions of southern stars to be known to a high degree of accuracy to assess their usefulness for computing positions or azimuths from them.

The Observatory grew to be one of the best equipped observatories in the Southern hemisphere to the extent of attracting from Sir George Airy in 1875 the comment “the Melbourne Observatory had produced the best catalogue of stars of the Southern Hemisphere ever published”.

In 1866 the marking of the eastern boundary line between Victoria and NSW [the Black – Allan line] became a matter of import due to the presence of gold mining activity in the highland streams and the uncertainty of which jurisdiction held sway in any particular area.

Although the line was officially described as that straight line between Cape Howe and the source of the Murray closest to it, the two terminals still required to be identified and marked on the ground. Ellery, in conjunction with the NSW Surveyor General, Mr P.F. Adams, eventually agreed on a rock outcrop as the physical identification of the Cape. Meanwhile, Mr Black [Geodetic Surveyor] had identified a particular spring as being the relevant source of the Murray. In early 1870, the triangulation was extended to connect both terminals with the triangulation network and the line between computed “with the greatest possible care”.

Ellery was also required to plan and organise observing parties for the 1874 transit of Venus. Four observing stations were employed – at the Observatory, at View Hill [Bendigo], at Glenrowan and at Mornington. Unfortunately the weather intervened and no complete series of observations were able to be completed at any of the stations.

Ellery was granted a week’s leave of absence from March, 1875 to recover from ill health and over work and went on a combined rest, recreation and study tour in England and Europe, taking the transit results with him and placing them in the hands of the Astronomer Royal [Airy] for computation together with those of the other British expeditions. With expeditions from Germany and the US, there was great international interest in the 1874 transit; the 1882 transit did not allow observation of the complete transit path in Australia as the passage had already commenced by sunrise on the relevant date.

Ellery was a member of the Royal Society and also, in 1878, was appointed Chairman of the Board of Examiners which examined the competency of Authorised Surveyors and heard complaints lodged against them. He was also the founding President of the Victorian Institute of Surveyors [1874 – 77]. Ellery certainly demonstrated those qualities which stand surveyors in good stead in any era, namely professionalism, intellectual curiosity, a wide interest in the geo-sciences and a dedication to public service.

The Observatory was virtually closed by 1944 with the retirement of the then Government Astronomer, with the major observing equipment being transferred to Mt. Stromlo.

Western Australia

William Frederick Rudall was a surveyor in the late 1890’s, with satellites, GPS’s and 4WD’s unheard of. He was only one amongst a very special group of hardy explorers who over the years travelled into remote corners of the deserts on camels and horses in order to find out what was out there. No-one knew initially but there were plenty of guesses made and the alluring thought of rich gold deposits spurred on many a hopeful expedition sponsor! Rudall’s observations were particularly accurate, recorded in journals that he kept while exploring. One of Rudall’s expeditions involved looking for 2 lost men from the Calvert Exploring Expedition (who were later found dead from thirst).

The journal from this search, near what is now called the Rudall River National Park in Western Australia, contains a passage in which he relates the basic method that he used to find his latitude using what he called a telescope. Rudall stated that he observed up to 6 stars at a time to take an average reading for latitude.

He described on 22 Dec 1896 the stars that he used, namely in the southern sky one called Canopus (Alpha Carinae) plus 2 northern stars called Capella (Alpha Aurigae) and nearby Aldebaran (Alpha Tauri). Gamma Hydri in the south and Alpha Arietis in the north were other common stars that he used on that expedition, most of which were stars that Len Beadell also commonly used over 50 years later. To further assist Rudall in keeping track of his location he measured his camels’ steps before departing in order to estimate the distance that they travelled each day. No odometers on a camel!

Queensland

In 1890, the Surveyor General of Queensland, Archibald McDowall decided to astronomically fix the position of the more important towns of the colony. McDowall realised that the triangulation survey of the colony, started in 1883, would not be feasible in western areas of Queensland, where the topography limited the setting of hill-top trig stations and atmospheric refraction interfered. It would be impossible to do good angular work except at certain times (for example early morning, evening or winter time).

In his annual report for 1890, he described why he has chosen astronomical fixes rather than triangulation to obtain data for accurate map compilation.

“At a more prosperous time, I should have advocated the contemporaneous continuance of both the astronomical and triangulating work, but under present circumstances, having chosen between two alternatives, and taking into consideration the compilation and engraving of the new map of the colony which will soon be necessary, I consider that the results we shall in a short time obtain from the astronomical work would be of much greater importance than those resulting from such a small extension of the triangulation”.

To this end, staff surveyors Robert Grant McDowall and Robert Hoggan were instructed to proceed to the northern towns of the colony to “fix” their positions (Lat-Long). They built their temporary observatories on the hill tops of these towns and commenced their work. For their observations, they used a twelve inch altazimuth theodolite made by Troughton and Simms, a chronograph, mean and sidereal chronometers furnished with electrical contacts for automatically sending the time signals. Local time was determined at each place by observing the zenith distances of east and west starts in pairs, the latitude being fixed by the method of ex-meridian altitudes.

The corresponding time in Brisbane (of known longitude) was determined at the Brisbane Observatory by Mr Cochrane, who used a 30 inch transit instrument for observing the meridional transits of stars, thus enabling the longitudes of the town to be determined.

20th Century

Desert surveyor Len Beadell, told of his adventures in the Australian bush, reading the stars with his theodolite and doing astrofixes to find out where he was in amongst a million square miles of scrub in order to make 6,500 thousand kilometres of road during the 1950’s and 60’s. Roads with quirky names like Gunbarrel Highway and those named after his children, the Connie Sue Highway, Gary Highway and Jackie Junction.

In a “Gibber Gabber” interview in 1952 (the local Woomera newspaper) Lennie had said that he never got lost in the bush because he could find his way by the aid of the stars. He had also joked that he went around in circles if it was cloudy and rainy.

Making roads in the desert is no small thing, especially before the days of modern 4WD’s and GPS’s. Len had a small party of men that he called “The Gunbarrel Road Construction Party” for a bit of fun. They made these roads in the harshest conditions possible. From Coober Pedy in the east, the Transcontinental Railway line in the south, “Carnegie” cattle station in the west and areas north of Alice Springs he made his roads, this after years already spent surveying in New Guinea during WWII.

Shortly after the war ended he was asked to start the surveys for the Woomera Rocket Range, and later the atomic sites of Emu and Maralinga. In a nutshell his early desert roads then criss-crossed the north-west centreline of fire for the rockets from Woomera and were for access into remote country for the placement of instruments and recovery of wreckage (the rockets did not always go where they were supposed to). Also necessary was the construction of weather stations to provide atmospheric data.

As the atomic program in Australia wound down the world-wide Geodetic Survey was in full swing to map the earth’s surface more accurately, so Len and his team were ideally placed to assist other surveyors in getting into country that very few had ever travelled into before. The stars made it all possible.

For Len, his astrofixes were the background for his entire work in the desert, as he put it, to “….handle a million square miles of unbroken horizons of sand hills to the skyline… ”. Star patterns are divided into constellations with individual stars named with Greek letters then the name of the constellation in which it falls, for example Alpha Centauri (any “Lost in Space” fan will have heard of that one). This star is the closest to earth at 4.3 light years away which is still very far away indeed, the distance to the moon from the earth a fraction in comparison.

Each star has a celestial co-ordinate like a Latitude & Longitude on earth. Len would read pairs of stars at night with his theodolite in order to determine the angle of the star from the horizon.

For latitude he would choose stars in the northern and southern skies, and for longitude he would look east and west. The stars he most wanted were about 40 degrees up from the horizon as these were the easiest to read with his theodolite. Using pairs of stars helped to correct for any distortions in the readings and the more pairs he used then the more accurate his mean result.

Once he had all the readings he required, with the additional use of a Nautical Almanac and time signals, he would do pages of sums to determine his position; just as well he was pretty good at maths! For his Woomera Rocket Range surveys he used around 20 stars each for Latitude and Longitude to determine a fix, which amounted to a lot of calculations but they gave him a much more accurate position.

Time signals were required during Longitude readings, which Len received via radio from Honolulu, and when accuracy was paramount he even compensated for the time it took for the radio signals to reach him which Len was told was approximately 0.08 seconds. For some of his surveys he only needed a few star fixes with latitude readings also possible during the day using the sun.

Nowadays, Len’s daughter Connie Sue and her husband Mick take tag-a-long tours out into the desert to introduce people to the country that Len, the early explorers before him, and age-old tribes of Aborigines travelled using the stars as their guide. If you would like more information on Len Beadell and tips for safe travel in the desert please go to their website at http://www.beadelltours.com.au.

Modern Science of Surveying

The size and shape of the Earth is now monitored continuously using GPS, satellite remote sensing, high accuracy gravity sensing and other high precision, space-based measuring techniques. These provide the framework to enable scientific observation of climate change, sea level rise, mass water transport and global tectonic motion studies for earthquake prediction.

This knowledge enables many other mapping applications from land, mining and engineering surveying to smart phone apps and Geographic Information System functionality. The convergence of these new high performance measurement technologies and unprecedented computing power has enabled what is being termed the “Geospatial Revolution”. Career opportunities abound and a new generation of surveying and spatial professionals are encouraged to study these disciplines at Universities and TAFEs across the country.

At a scientific level, much like the Transits of Venus of the 1700s, the science of Geodesy studies the shape and gravity field of the Earth and its changes. Knowledge of local gravity in a region is an excellent tool for mineral exploration.

Ground and space-based geodetic measurements investigate Earth rotation and polar motion, and even the tidal effect of the Earth’s crust. Geodesy also computes the orbits of geodetic satellites for the analysis and prediction of processes involving the oceans, atmosphere and internal processes in the solid Earth. A new area is 3D georeferencing using combined global, inertial and imaging sensors for navigation, mapping and GIS applications both indoors and outdoors.

Will we one day see a Harry Potter style Marauder’s Map produced by Surveying and Spatial graduates?

The advances in geodetic knowledge trickle down to surveying and spatial professionals who benefit from this cutting edge scientific work everyday.

New Technology and their applications

The advancement of new technology is being embraced by Surveyors who can now take measurements and report data with increased speed and accuracy. Indeed they are increasingly being seen as spatial data managers.

Surveyors use equipment like robotic total stations, worth upwards of $50K, to electronically measure angles and distances and produce 3D models of natural and man-made features. They use laser scanners that can measure clouds of points (sometimes 500,000/ second (!!)) for very complex industrial structures to mm accuracy. Aerial and terrestrial digital photography can now be used for small and large scale projects and even with Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs).

Surveyors are being asked to locate underground utilities to avoid power and communications blackouts in cities. Spatial scientists are crucial during fire and flood emergencies as they can provide accurate and up-to-date spatial information to optimise relief efforts.

Mining surveyors are in short supply across Australia as we ride the mining boom. Their spatial overview optimises mining operations and ensures maximum productivity.

New technologies are transforming the work of the modern surveyor with opportunities expanding more broadly than ever!

Conclusion

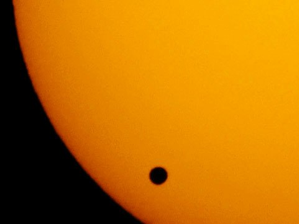

The transit of Venus and the total solar eclipse, both occurring in 2012, are ideal ways to become familiar with the work of surveyors. The convergence of the modern science of surveying with these new high performance technologies and unprecedented computing power has enabled what is being termed the “Geospatial Revolution”.

Career opportunities abound and a new generation of surveying and spatial professionals is encouraged to study these disciplines at Universities and TAFEs across the country.

References

Annual Reports of the Astronomer to the Board of Visitors, 1860, 1875, 1876, 1882. Government Printer.

Chappel, Keith L. [1966], Surveying for Land Settlement in Victoria 1836 – 1960. Surveyor General Victoria.

Gribbin, John [2006], History of Western Science 1543 – 2001, Folio.

Haynes, Raymond, Haynes, Roslyn, Malin, David, McGee, Richard [1996], Explorers of the Southern Sky – A history of Australian Astronomy.

Kitson, William, McKay Judith [2006] Surveying Queensland 1839 – 1945: A Pictorial History

Ronan, Colin A. [1983], The Cambridge Illustrated History of the World’s Science, Cambridge – Newnes

Sutherland, Alexander [1888], Victoria and its Metropolis, Past and Present, Vol. II. McCarron, Bird & Co.